No Products in the Cart

So, can you transport gas cylinders lying down? The short answer is yes, but it’s a qualified yes. This method is strictly reserved for specific situations and demands careful adherence to safety protocols. It’s a common approach for cryogenic liquids, while compressed gases almost always have to travel upright.

The real key is knowing exactly which gas you're dealing with and the specific rules that apply to it.

Deciding to transport a gas cylinder horizontally isn’t about what’s most convenient; it’s dictated entirely by the physical state of the gas inside. For anyone managing a lab, coordinating logistics, or handling cylinders directly, getting this wrong introduces some serious risks, from equipment damage to critical safety failures.

Think about compressed gases like oxygen, argon, or nitrogen. They're stored under incredibly high pressure in a gaseous state. If you lay these cylinders down, you run the risk of exposing the pressure relief valve—which is designed to handle gas—to any liquid that might have condensed inside. This can cause the valve to malfunction or fail completely, which is why upright transport is the non-negotiable standard.

Cryogenic liquids, like liquid nitrogen (LN2), are a completely different ball game. These are extremely cold liquids that are constantly boiling off into gas. They are often transported horizontally in specialised, vacuum-insulated vessels. This position creates a lower centre of gravity, making the entire load far more stable during transit. For biobanks and labs moving highly sensitive biological samples, that stability is everything.

In Germany, the rules for gasflasche liegend transportieren (transporting a gas cylinder lying down) are governed by the ADR—the European Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road. These regulations are strict, but they're also built for the real world.

For example, certain insulating gases use a system where each kilogram is assigned an evaluation point. This allows up to 1,000 points (or 1,000 kg) to be moved without needing a full dangerous goods licence or vehicle markings. For smaller labs and biobanks, this is a massive practical advantage. You can find more details on these transport regulations over on the DILO website.

The core principle is simple: Stability and safety first. A lower centre of gravity reduces the risk of tipping, which is a significant advantage when moving heavy or bulky cylinders, especially in vehicles with limited height.

To help clarify the decision-making process, here’s a quick comparison of the two transport methods.

This table breaks down the essential differences between transporting gas cylinders horizontally versus keeping them upright, giving you a clear guide for different gas types and scenarios.

| Transport Position | Best Suited For | Key Safety Consideration | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal (Lying) | Cryogenic liquids (e.g., LN2) and some specialised gases in purpose-built vessels. | Must ensure valve is not submerged in liquid; use proper cradles or blocks to prevent rolling. | Biobanks transporting samples in cryogenic dewars; industrial applications with large, stable vessels. |

| Upright (Standing) | Compressed gases (e.g., oxygen, argon, helium) and liquefied petroleum gases (LPG). | Must be secured with straps, chains, or racks to prevent tipping or falling over during transit. | Medical gas delivery to hospitals; welding gas transport to construction sites; laboratory gas supply. |

Ultimately, choosing the correct orientation is a fundamental step in risk management for your operations.

Making the wrong choice can lead to a host of problems:

On the flip side, when horizontal transport is done correctly and for the right type of gas, it offers enhanced stability and is often the only compliant way to move certain cryogenic vessels. Getting this distinction right is the bedrock of safe cylinder handling.

When you're planning to transport gas cylinders horizontally, or gasflasche liegend transportieren as it's known here in Germany, you're not just making a simple logistical decision. You're stepping directly into the world of ADR regulations—the European Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road.

These aren't just gentle guidelines; they are legally binding rules designed to keep everyone safe. For any lab manager, biobank operator, or industrial user, getting a solid grasp on these regulations isn't just good practice—it's essential for staying compliant and preventing accidents.

At first glance, the ADR framework can seem pretty dense. But its core purpose is actually quite straightforward: risk management. It categorises dangerous goods, lays out exactly how they need to be packaged and secured, and details the specific paperwork you'll need for the journey.

One of the most useful parts of the ADR for smaller-scale transport is what's known as the "1,000-point rule" (1.000-Punkte-Regel). This is a game-changer for labs and biobanks that don't run a dedicated fleet of logistics vehicles, as it offers exemptions from some of the more intense ADR requirements.

Here’s how it works: every dangerous substance is assigned a point value per kilogram or litre. If the grand total of your entire load stays below 1,000 points, you can often get away with transporting it without needing a specially marked vehicle or a driver with a full-blown ADR licence.

Let's walk through a common scenario. Imagine a biobank needs to shift three liquid nitrogen transport vessels over to a partner facility.

Liquid nitrogen falls under Transport Category 3, which comes with a multiplier of 3. The calculation is simple: just multiply the total volume by 3.

Since 360 is comfortably under the 1,000-point limit, this entire transport qualifies for the exemption. This means the biobank can use a standard vehicle—no orange warning plates needed—as long as all the other critical safety steps, like proper securing and ventilation, are handled correctly. For a much deeper dive into these rules, you can explore the detailed regulations for transporting gas cylinders in our dedicated guide.

Even when you're operating under the 1,000-point rule, you're not completely off the hook. There’s some paperwork that is absolutely non-negotiable and must be with the driver at all times.

You need a transport document that clearly lists:

On top of that, having a 2 kg fire extinguisher is mandatory for any vehicle carrying dangerous goods, regardless of whether you’re under the 1,000-point limit.

Now, if your load does go over that 1,000-point threshold, things get a lot more serious. You'll then need:

Key Takeaway: The 1,000-point rule is a fantastic exemption, but it's not a free-for-all. You still always need the right documents, a fire extinguisher, and securely loaded cylinders. Cutting corners here can lead to hefty fines and serious legal trouble.

Frankly, using equipment that's already designed and certified for ADR transport just simplifies everything. Specialised transport vessels, like the ones in our AC LIN series, are built from the ground up with the realities of road transport in mind. They have robust construction and integrated securing points that make tying them down properly a breeze.

What’s more, German regulations like TSG23-2021 and UN GTR No. 13 for liquefied hydrogen—which is a good parallel for LN2—explicitly permit horizontal mounting, provided the cylinders pass stringent crash tests for leakage. The numbers really back this up. Incidents caused by improperly secured upright cylinders dropped by a staggering 30% between 2015 and 2020 after horizontal transport was mandated for loads under 1,000 points.

When you invest in ADR-compliant dewars, you’re not just buying a container. You're buying peace of mind, knowing your equipment is built to the highest safety standards required for moving these sensitive—and potentially hazardous—materials.

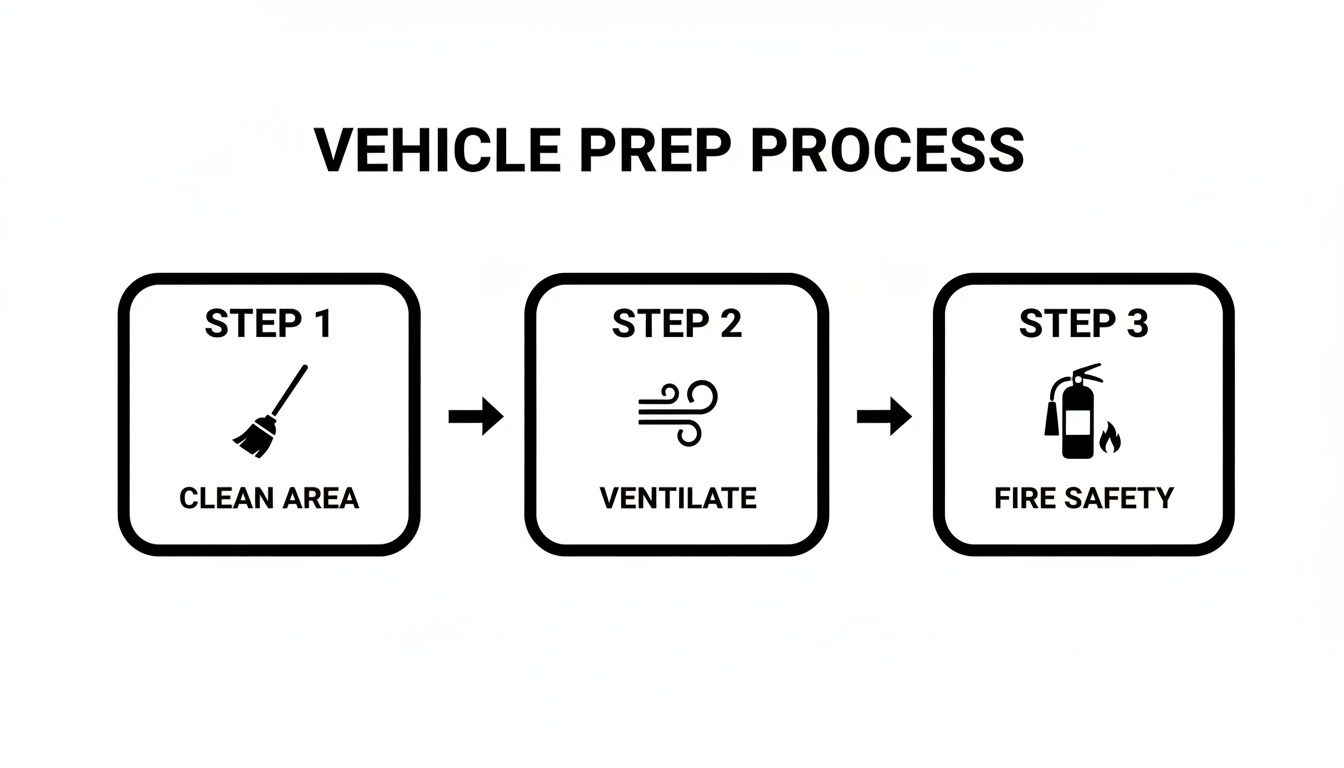

Before you even think about moving a cylinder, your vehicle has to be made ready. This is more than just making some space in the back; it's about methodically prepping your van or truck to handle the specific risks involved. If you skip this part, any other safety steps you take are built on a shaky foundation.

First things first: get in there and give the transport area a thorough inspection and clean-out. Clear away any loose tools, rubbish, or other bits and pieces that could slide around and bash into a cylinder. The surface where the cylinder will rest needs to be perfectly flat and, critically, free from any sharp objects. A stray screw or a metal burr could easily score or damage the cylinder wall during transit.

This simple clean-up job creates a controlled, predictable space, which is the absolute baseline for transporting gas safely.

Proper ventilation is completely non-negotiable, particularly if you’re moving inert gases like nitrogen or argon. In an enclosed space like a van, even a tiny, slow leak can displace oxygen and create a deadly atmosphere in just a few minutes. It's a silent, invisible threat, which makes good ventilation your first and best line of defence.

For an enclosed van, cracking a window just doesn't cut it. The best-case scenario is a dedicated ventilation system, like a roof-mounted rotary vent, which actively pulls air out of the cargo area. If you don't have one, you absolutely must create cross-ventilation by keeping windows open on opposite sides of the vehicle to maintain a constant flow of fresh air.

Things are a bit different with an open flatbed truck, where the open air provides natural ventilation. Your job here shifts to protecting the cylinders from weather and road debris while still allowing any potential leaks to blow away harmlessly. For a more detailed look at the rules, especially for smaller loads, our guide on transporting gas cylinders in a car has some extra practical tips.

Ventilation isn't just a good idea; it's a critical safety measure. A review of workplace incidents involving gas transport revealed that over 60% of accidents in enclosed vehicles were tied to poor ventilation, resulting in asphyxiation or fire.

Having the right fire extinguisher on board isn’t just an ADR requirement—it’s basic common sense. The type you need is directly linked to the gas you're carrying. While a 2 kg ABC dry powder extinguisher is the minimum for most jobs falling under the 1,000-point rule, the specific gas you're hauling might call for something more.

For instance, if you're transporting flammable gases, your fire prep needs to be even more rigorous. Make sure the extinguisher is:

Making this check part of your pre-loading routine turns a tick-box exercise into a solid safety habit. Before the first cylinder is even loaded, your vehicle should already be a prepared, ventilated, and fire-safe environment. This systematic approach tackles risks right from the start.

Let's be clear: securing a gas cylinder correctly is a non-negotiable part of the transport process. It's a precise skill that counters the inherent risks you face when you gasflasche liegend transportieren (transport a gas cylinder lying down). You’re dealing with a heavy, smooth, and perfectly round object that’s just waiting for a chance to roll or slide. Your one job is to make sure that simply can't happen.

Generic advice like "tie it down well" is dangerously inadequate. We need to get specific and look at the right tools for the job—ratchet straps, chocks, and specialised racks—and, more importantly, how to use them the right way. The core principle is simple: create a single, rigid, unmoving unit within your vehicle.

Before you even think about loading the cylinder, your vehicle needs to be prepped. It’s a foundational step that many people overlook.

This process isn't just a suggestion; it's about creating a safe environment. A clean, well-ventilated, and fire-safe space is the bedrock upon which all your other securing efforts are built.

The method you pick really depends on your specific situation: the type of vehicle you have, how many cylinders you're moving, and how often you're doing it. A one-time trip for a single cylinder might just need some solid chocks and straps. But if you’re running a daily delivery route, investing in a purpose-built rack is a much smarter move.

Your goal is to eliminate any possibility of movement—not just side-to-side rolling but also front-to-back sliding. In my experience, a combination of methods, like using chocks to prevent rolling and straps to stop sliding, offers the most robust and reliable solution.

Choosing the right tool is the first step. Below is a quick comparison to help you decide what's best for your needs.

| Securing Method | Stability Rating (1-5) | Best For | Potential Pitfall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ratchet Straps (x2) | 4 | Versatile; securing 1-3 cylinders in vans or trucks. | Requires proper technique (X-pattern); risk of overtightening. |

| Chocks/Blocks | 3 | Preventing roll in combination with straps; short, low-speed trips. | Does not prevent sliding on its own; can shift on slick surfaces. |

| Purpose-Built Racks | 5 | Daily/frequent transport; companies moving multiple cylinders. | Higher initial cost; permanently installed in the vehicle. |

| Bungee Cords/Rope | 0 | NEVER USE | Fails under load; offers a false sense of security. |

As you can see, purpose-built racks offer the most stability, but a well-executed strapping and chocking method is highly effective for most users.

How you position the cylinder is just as crucial as how you tie it down. The golden rule is simple: the valve must always be protected. When you lay a cylinder horizontally, position it so the valve cap points away from the main direction of travel, usually towards the side of the vehicle.

This simple orientation trick shields the cylinder's most vulnerable point from a potential frontal impact. It goes without saying, but always double-check that the protective cap is screwed on tight. If you want to dive deeper into why these caps are so critical, have a look at our guide on the proper use of a gas cylinder protective cap.

When it comes to strapping, please avoid just throwing a single strap over the middle. This does next to nothing to stop the cylinder from sliding forward during a sudden brake.

A far superior approach is using two straps in an "X" pattern across the cylinder's body. This crisscross technique applies downward pressure while also bracing against forward and backward forces, effectively locking the cylinder against the floor and chocks.

Make sure you're connecting the straps to solid anchor points on the vehicle’s chassis—not flimsy plastic trim or thin sheet metal. Those factory-installed anchor points are designed to handle immense force.

Many accidents aren't due to a lack of effort, but rather from using the wrong technique. Over the years, I've seen a few common—and incredibly dangerous—mistakes people make when they try to gasflasche liegend transportieren.

Getting the physical securing right is the final, critical piece of the puzzle. It transforms your vehicle from a simple box on wheels into a safe transport system, ensuring your cylinders arrive exactly as they were loaded: stable, secure, and intact.

A safe, compliant journey with a gas cylinder doesn’t just happen between ignition and arrival. It's a process bookended by disciplined, systematic safety checks. Skipping these inspections is like an airline pilot skipping the pre-flight check—it introduces serious risks that are so easily avoided.

These routines are your best guarantee that when you need to transport a gas bottle lying down (or gasflasche liegend transportieren as it's known in German regulations), you can be confident it was safe when loaded and remains safe when unloaded.

Before a cylinder even gets near your vehicle, a quick but thorough inspection is non-negotiable. This isn’t a casual glance; it's a deliberate hunt for specific issues that could escalate into major problems on the road. You’re looking for anything that might compromise the cylinder’s integrity.

Your visual check should focus on these key areas:

Once the visual check is done, physically confirm the valve is completely closed. Even if you assume it's shut, give the handwheel a firm but gentle clockwise turn to be absolutely sure. The final step is to screw on the protective valve cap until it is hand-tight. That cap isn't just for decoration; it’s a critical piece of safety gear designed to prevent the entire valve assembly from being sheared off in an impact.

With the visual inspection out of the way, a leak check gives you that final piece of pre-departure assurance. This is especially important for cylinders that might have been sitting in storage. You don’t need any fancy equipment for this—a simple solution of soapy water does the job perfectly.

You can grab a commercial leak detection spray, or simply mix some washing-up liquid with water in a spray bottle. Apply the solution generously around the valve stem, the outlet connection point, and the pressure relief device.

Pro Tip: Watch closely for bubbles forming, which can range from a tiny fizz to large, obvious bubbles. Bubbles mean escaping gas. If you spot a leak, do not transport the cylinder. Move it to a well-ventilated area, isolate it, and call your gas supplier immediately.

This simple test takes less than a minute but can prevent a hazardous gas build-up inside your vehicle. It’s an essential habit for anyone handling compressed or cryogenic gases.

Your job isn't done the moment you park. The post-transport check is just as vital as the pre-departure one. The journey itself—with all its vibrations, bumps, and strains—can introduce new problems, from loosened fittings to damage caused by securing straps.

First things first: carefully unstrap and unload the cylinder. Never, ever roll or drop a cylinder from the vehicle bed. Always use a proper trolley or lifting equipment to prevent injury to yourself and damage to the cylinder.

With the cylinder safely on the ground, repeat the same thorough visual inspection you did before you left. You're looking for any new damage that might have happened during the trip. Pay extra attention to the valve area and the points where the straps were making contact.

This final check confirms the cylinder has survived the stresses of the road and is safe for use. Once it passes inspection, move it to its designated storage spot—a secure, well-ventilated area away from traffic, heat sources, or potential ignition. This completes the safety cycle, ensuring the cylinder is ready and waiting safely for its next task.

Even with the best guide, theory and real-world practice are two different things. Specific questions always pop up when you're on the ground, dealing with the practical side of moving gas cylinders, especially when you need to transport one horizontally (gasflasche liegend transportieren).

This section tackles the most frequent questions we hear from technicians, lab managers, and drivers. Think of it as the troubleshooting part of the guide, designed to give you quick, clear answers for those tricky situations you'll inevitably face.

This is easily the most common question we get, particularly for personal or occasional use. The answer is a hard no. Standard propane (LPG) cylinders are designed and built for one orientation only: upright.

Here’s why: when you lay a propane cylinder on its side, the liquid propane inside sloshes around and can easily cover the pressure relief valve. That valve is engineered to vent gaseous propane in an over-pressure situation, not liquid. If the valve has to operate while submerged in liquid, it can malfunction, leading to a dangerous leak or, in the worst-case scenario, catastrophic failure. Always, always keep standard propane cylinders upright and securely fastened.

That protective valve cap isn't just a suggestion; it’s arguably the most critical piece of safety hardware on the entire cylinder. The valve assembly is, by design, the cylinder's most vulnerable point. If an uncapped cylinder gets knocked over, the valve can be sheared clean off.

When that happens, the cylinder instantly becomes an unguided, high-pressure rocket. We're talking enough force to punch through concrete walls. Safety incident reports have shown an unsecured, uncapped cylinder can accelerate to over 50 km/h in a fraction of a second. This is exactly why the pre-transport check—making sure that cap is screwed on tight—is completely non-negotiable.

Always treat an uncapped cylinder as an immediate and serious hazard. The simple act of screwing on the cap before you even think about moving it reduces the risk of a catastrophic accident to nearly zero. It's the single most effective safety habit you can build.

A high-friction rubber mat is a fantastic piece of kit, but it is not a standalone securing method. Its real job is to stop the cylinder from sliding around on a smooth metal floor, which in turn makes your straps far more effective.

You have to think of it as part of a complete system:

Relying on just one of these elements gives you a false sense of security. You need all three working in concert to ensure that cylinder remains completely immobile for the entire journey.

Your securing equipment deserves just as much attention as the cylinders themselves. Ratchet straps aren't a "set it and forget it" item. They take a beating from friction, UV light, moisture, and constant tension.

A quick visual inspection should be part of your routine before every single use. Look for:

If you spot any of these problems, take the strap out of service immediately. The cost of a new strap is nothing compared to the potential cost of an accident caused by a strap that failed. For vehicles in regular, daily use, we recommend making it a policy to replace straps annually, regardless of how they look. This proactive approach takes the guesswork out of the equation and maintains the highest safety standard for every transport.

At Cryonos GmbH, we understand that safe transport is just as important as secure storage. Our ADR-compliant transport vessels and cryogenic equipment are engineered to meet the highest safety and regulatory standards, giving you peace of mind on the road. Explore our solutions for labs, biobanks, and industrial users.