No Products in the Cart

Yes, you can transport gas cylinders lying down—but it's not a simple case of just tossing them in the back of your van. While keeping cylinders upright is always the safest and preferred method, laying them down (gasflaschen liegend transportieren) is allowed under specific, strict conditions laid out by the ADR (European Agreement Concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road).

The game-changer here is the 1,000-point threshold. Get this right, and the process is manageable. Get it wrong, and you're suddenly in a world of complex regulations.

Figuring out the rules for horizontal transport can feel a bit like navigating a maze, but it really boils down to a few key things. These regulations are all about one thing: safety. It doesn't matter if you're moving industrial gases to a job site, medical oxygen for a clinic, or cryogenic vessels for a lab—the core principles are the same.

The decision almost always hinges on the type and total amount of gas you're hauling. This is where that ADR points system comes into play. Every hazardous material gets a point value based on its risk. If your entire load stays below 1,000 ADR points, you're generally exempt from the big stuff, like needing special vehicle placards or a dangerous goods driving licence. This exemption is what makes horizontal transport a realistic option for smaller loads.

So, how do you know if your plan is compliant? You need to look at the whole picture:

Here in Germany, the ADR regulations are taken very seriously. For example, if you're using an open vehicle or trailer, you can often transport cylinders up to 50 litres horizontally. They can be laid either parallel or perpendicular to the vehicle's direction of travel, but only if you don't exceed the vehicle's load capacity and—you guessed it—you stay under that 1,000-point limit. For a deeper dive, the ADR pocket guide from Messergroup is an excellent resource.

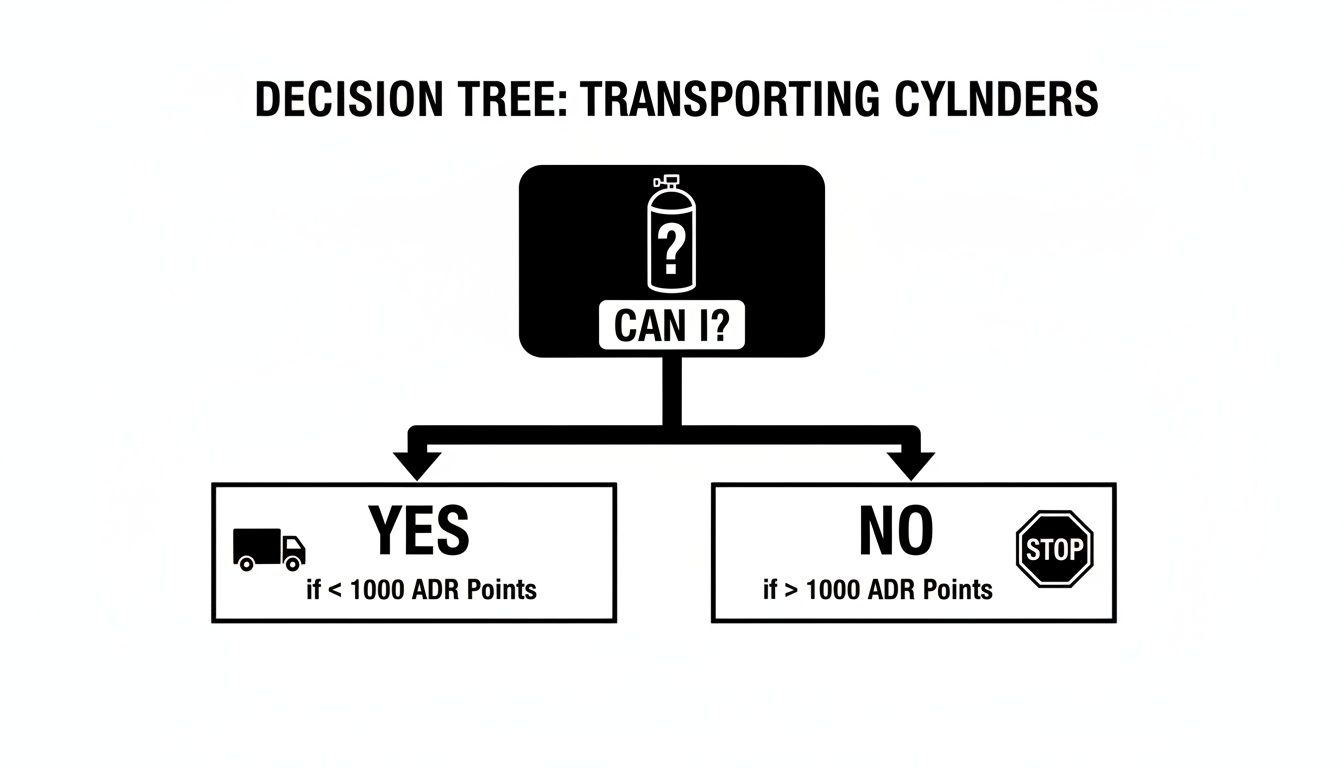

This decision tree gives you a quick visual to see if you fall under the 1,000-point exemption.

As you can see, tipping over the 1,000-point mark changes everything. At that point, full ADR compliance is mandatory, and upright transport in a properly kitted-out vehicle becomes non-negotiable. Staying below the threshold gives you the flexibility to choose horizontal transport, as long as you have every other safety measure nailed down.

Sometimes a quick comparison is the easiest way to see which method fits your situation. This table breaks down the key considerations for both horizontal (liegend) and upright transport.

| Factor | Horizontal Transport (Liegend) | Upright Transport |

|---|---|---|

| When to Use | Small quantities, under the 1,000 ADR point threshold, or when vehicle height is limited. | The standard and safest method for nearly all situations, mandatory for large quantities. |

| ADR Regulations | Permitted under the "small quantity exemption" (1.1.3.6 ADR) if points are below 1,000. | Always compliant, but requires full ADR rules (placards, driver training) if over 1,000 points. |

| Securing Method | Requires specialised cradles or blocks, straps, and padding to prevent rolling and impact. | Requires racks, stands, or secure strapping to a fixed point in the vehicle. |

| Vehicle Type | Possible in open vehicles or well-ventilated vans with proper equipment. | Best practice for dedicated transport vehicles, vans, and trucks with adequate height. |

| Key Risk | Valve damage from rolling or shifting; potential for liquid phase gas to enter the regulator. | Tipping over if not properly secured, leading to high-impact damage. |

Ultimately, while horizontal transport has its place for specific, limited scenarios, upright transport remains the gold standard for good reason. It minimises the most critical risks and is the only compliant option for larger, professionally managed loads.

Navigating the ADR points system isn't about complex maths; it’s about understanding risk. The easiest way to think about it is to treat the 1,000-point limit as your transport "budget". Every cylinder you load uses up some of that budget. Your main job is to stay under that 1,000-point threshold to avoid triggering the full, far more complicated dangerous goods regulations.

For any business dealing with gases—whether you're in cryogenics, welding, or industrial supply—getting a firm grip on this system is fundamental to efficient and legal operations. It directly impacts how much you can carry, what vehicle you can use, and the paperwork you'll need. A solid approach to transportation risk management is non-negotiable.

The calculation itself is refreshingly simple: the more hazardous the gas, the more points it costs per kilogramme. This design is clever because it forces you to treat a small amount of a highly dangerous gas with the same seriousness as a large load of a less volatile one.

Let’s put this into practice. Say you're moving Sulfur Hexafluoride (UN1080), a common non-flammable gas used in the electrical industry. This falls into Transport Category 3, which costs just 1 point per kilogramme. Do the maths, and you'll see you can transport up to 1,000 kg before you need to worry about full ADR compliance.

But what if you're dealing with something far nastier, like Boron Trifluoride (UN1008)? That's in Transport Category 1, and its point value skyrockets to 50 points per kilogramme. Suddenly, your maximum load plummets to just 20 kg (20 kg x 50 points = 1,000 points). This massive difference perfectly illustrates how the system is built around hazard levels.

Key Takeaway: The ADR point system isn't just bureaucratic red tape. It’s a practical, risk-based framework that shapes your entire logistics plan. Knowing the points for your gases lets you plan loads that stay within the exemption, saving you a world of hassle, time, and money.

To give you a clearer picture, here’s how ADR points work out for a few common gases. Notice how quickly the maximum quantity drops as the points-per-kilogramme figure rises.

| Gas Type (UN Number) | Points per Kilogramme | Max Quantity Before Full ADR (kg) |

|---|---|---|

| UN1977 (Nitrogen, refrigerated liquid) | 1 | 1,000 kg |

| UN1072 (Oxygen, compressed) | 3 | 333 kg |

| UN1956 (Compressed gas, n.o.s.) | 3 | 333 kg |

| UN1001 (Acetylene, dissolved) | Special Rules Apply | Not based on weight alone |

| UN1076 (Phosgene) | 50 | 20 kg |

As you can see, you can move a full tonne of liquid nitrogen under the exemption, but just a small 20 kg cylinder of phosgene pushes you into full ADR territory.

The vehicle you choose is every bit as important as the points you’re tallying. The rules for a private car versus a commercial van are worlds apart, and for very good reason—each one has a completely different risk profile.

German regulations, for example, are incredibly specific. You can transport cylinders horizontally in an enclosed commercial van with a separate, properly ventilated cargo area right up to the vehicle's maximum load capacity (as long as you stay under 1,000 points). But take away that ventilation, and the limit drops to just 200 kilogrammes. For a private car, the rules are even tighter: a maximum of 50 kilogrammes in the boot. For a deeper dive, our detailed guide covers all the official transport regulations for gas cylinders.

This is where the term gasflaschen liegend transportieren (transporting gas cylinders lying down) really comes into play. These rules are not arbitrary; they're designed to prevent a disaster. A minor leak in a ventilated van is an issue, but that same leak inside a sealed car could be fatal. Inert gases can quickly displace oxygen, creating a serious asphyxiation risk for anyone inside.

This is why open vehicles, like pickup trucks, often provide the most straightforward option for transporting cylinders under the 1,000-point rule. They naturally prevent any dangerous accumulation of gas, making them a much safer choice.

When you decide to transport a gas cylinder lying down (gasflaschen liegend transportieren), getting the securing part right is your most important job. This goes way beyond just stopping a heavy cylinder from rolling around. It’s a deliberate process designed to protect the most vulnerable—and most dangerous—part of the cylinder: the valve assembly.

A sudden stop or even a sharp turn can turn an unsecured cylinder into a missile. If that valve gets hit and shears off, the cylinder instantly becomes an uncontrolled rocket, venting high-pressure gas with catastrophic force. Proper securing is the only thing standing between a routine trip and a disaster.

Before you even reach for a strap, the very first step is to check the valve protection cap. This heavy-duty steel or composite cover isn’t just an accessory; it’s a mandatory piece of safety gear under ADR regulations, and for a very good reason.

Its one and only job is to shield the valve from a direct hit. When a cylinder is lying flat, its valve is far more exposed than when it's standing up. The cap is that crucial barrier, built to absorb and deflect impacts that could otherwise snap the valve clean off.

Driving with a cylinder lying down without its cap screwed on tight isn't just a bad idea—it's a serious legal and safety violation. If you want a deeper dive, our guide on why a gas cylinder protective cap is essential explains it all.

Always twist the cap on by hand until it's completely firm. It needs to be much tighter than just finger-tight to make sure road vibrations don’t work it loose.

Let's be clear: generic bungee cords or a bit of old rope are useless for this task. You need equipment specifically designed to handle the serious weight and forces involved. Your kit for securing cylinders horizontally should include some combination of these:

Expert Tip: Never underestimate inertia. A 50 kg cylinder in a vehicle that brakes hard from just 50 km/h can exert a forward force equal to hundreds of kilogrammes. Your securing gear has to be strong enough to absorb that massive, sudden load.

How you orient the cylinders in your vehicle makes a big difference to how stable they are. There are two main ways to do it, and the best choice depends on your vehicle's layout.

Placing cylinders across the width of your vehicle (perpendicular to the direction of travel) is usually the most secure option.

Laying cylinders along the length of the vehicle (parallel to the direction of travel) is also common, especially in longer vehicles or when you’re carrying a few cylinders side-by-side.

No matter which way you orient them, the final goal is zero movement. Once you think you're done, give the cylinders a good, firm shove from a few different angles. If you can make them shift or roll even a little, they aren't secure enough. Go back, re-tighten your straps, adjust your chocks, and get rid of all the slack until the load is completely solid.

Before you even think about turning the key, a few minutes spent on a thorough check can be the difference between a routine trip and a disaster. This isn't bureaucracy; it's a vital process that should become second nature for anyone moving gas cylinders, especially when they’re lying down. Rushing this step is a gamble you can't afford to take.

Part of this routine involves giving your vehicle and equipment a proper once-over. Running through some detailed pre-trip inspection procedures confirms everything is in solid working order before you load up hazardous materials.

Start by giving the cylinder itself a good, hard look. You’re hunting for any red flags that hint at structural weakness or a potential failure.

If a cylinder looks dodgy, don't use it. If you have any doubt about its integrity, leave it behind.

Happy with the cylinder's condition? Now it's time to make sure every safety measure is locked in tight. This is your last chance to catch an oversight before you hit the road.

First, confirm the cylinder valve is shut tight. A firm clockwise turn should do it. Don't go overboard with a wrench or you risk damaging the seal.

Next, check the valve protection cap. It needs to be screwed on securely—much more than just finger-tight—so it won’t vibrate loose. When a cylinder is horizontal, that cap is the valve's only real protection from an impact.

Finally, give your securing straps a proper shakedown. Push and pull on the cylinder from every angle. It should have zero movement. If you can get it to shift, roll, or even slide an inch, your restraints aren't good enough. Get back in there and tighten everything until the load is rock solid.

Crucial Reminder: Complacency is the enemy of safety. Even if you've done this a thousand times, treat every single transport like it's your first. Be deliberate and never, ever assume something is "good enough."

Even with the best preparation, you have to be ready for the worst-case scenario. Knowing what to do in an emergency is just as important as securing the load in the first place.

Make sure all your necessary documents are within easy reach—not buried under a pile of gear in the back. This means your transport documents and, most importantly, the Safety Data Sheets (SDS) for the gases you're hauling. These sheets give emergency services the critical info they need.

So, what do you do if you hear a hiss or smell gas? The key is to act immediately but stay calm.

Having a clear plan for a leak is non-negotiable. The goal is to contain the situation and let the trained professionals handle the hazard.

The world of gases isn't one-size-fits-all. While the rules for standard compressed gases like oxygen or argon are fairly straightforward, everything changes when you enter the realm of cryogenic liquids. Moving a dewar of liquid nitrogen (LIN) is a completely different ball game than shifting a cylinder of CO₂, and these differences are absolutely critical for safety.

For anyone working in biobanking, cell therapy, or pharmaceuticals, this isn't just trivia—it's essential knowledge. The integrity of priceless biological samples often hinges on maintaining cryogenic temperatures, making a solid understanding of how to transport these specialised vessels non-negotiable.

With cryogenic liquids, keeping the vessel upright during transport isn't just a suggestion; it's the gold standard and, for the most part, a requirement. The reason boils down to physics and the design of the safety valves.

Cryogenic vessels, which you'll often hear called dewars, are basically high-tech thermos flasks built to hold liquids at incredibly low temperatures. They're designed to safely vent tiny amounts of gas as the liquid naturally evaporates and pressure builds. This is all handled by a pressure relief valve system, which is always at the top of the dewar.

If you lay a dewar on its side, the super-cold liquid can slosh around and come into direct contact with this valve. This leads to two immediate and serious dangers:

This is exactly why organisations handling sensitive materials, from animal breeders to biotech firms using products like the Cryonos GmbH AC LIN series, must make upright transport a priority. These ADR-compliant dewars are engineered to perform best when kept vertical. To get a better sense of why these fluids require such careful handling, you can read our deep dive on just how cold liquid nitrogen is.

Despite the strong preference for keeping things upright, there are a few specific, limited scenarios where certain cryogenic vessels can be transported horizontally under ADR rules. This usually only applies to smaller, specially designed "dry shipper" dewars. These contain an absorbent material that soaks up the liquid nitrogen, preventing it from sloshing around.

Even then, the conditions are strict. The practice of gasflaschen liegend transportieren in Germany aligns with ADR for many non-liquid gases, but liquid nitrogen has its own unique demands. Although upright positioning is paramount, horizontal transport of certain approved vessels is possible under specific load limits and securing protocols.

Important Takeaway: Always, always check the manufacturer's specifications for your specific dewar. If it's not explicitly certified for horizontal transport, you must move it upright. No exceptions.

Another vital distinction to make when thinking about horizontal transport is between compressed and liquefied gases. They behave very differently inside the cylinder, which completely changes the risk profile.

A compressed gas, like nitrogen or helium, exists purely as a gas inside the cylinder, even at high pressure. This means its behaviour is pretty consistent no matter how the cylinder is oriented. As long as you protect the valve from physical damage, laying it down is generally fine under ADR exemption rules.

A liquefied gas, such as propane or carbon dioxide, is a different story. It exists as a liquid at the bottom of the cylinder with a layer of gas vapour on top. The moment you tilt that cylinder horizontally, the game changes.

Here’s a quick look at the key differences:

| Feature | Compressed Gas (e.g., Oxygen) | Liquefied Gas (e.g., Propane) |

|---|---|---|

| State Inside Cylinder | Exists only as a gas. | Exists as both liquid and gas. |

| Pressure Behaviour | Pressure drops steadily as gas is used. | Pressure stays constant until all liquid has evaporated. |

| Risk in Horizontal Transport | The main risk is physical damage to the valve. | High risk of liquid entering the valve and regulator system. |

| Valve System | Standard valve designed for gas flow. | Often has a pressure relief valve that must not contact liquid. |

If liquid from a liquefied gas cylinder gets into the regulator, it can freeze and damage the equipment, which could lead to an uncontrolled and dangerous release of gas.

This is why for certain liquefied gases, especially tricky ones like acetylene (which is dissolved in a solvent), upright transport is mandatory. Acetylene cylinders must always be kept vertical to stop the stabilising acetone solvent from separating, an event that could lead to an explosive decomposition. Before you move any cylinder, double-check the specific rules for that gas.

Even with the best plan, questions always pop up when you're about to load gas cylinders on their side. Getting straight answers is vital for handling every situation safely and by the book. Let's tackle the most common things people ask when they need to gasflaschen liegend transportieren.

Technically, yes, but the rules are incredibly strict for a very good reason. German regulations cap the total weight at a firm 50 kilograms for gas cylinders in a private car. And they must be in the boot—never in the passenger cabin—and locked down so they can't move an inch.

Ventilation is the other big worry. A tiny, silent leak from an inert gas like argon can displace the oxygen in your car in a flash, creating a deadly asphyxiation hazard. Honestly, given the risks, if you're moving anything more than a small cylinder, using a proper commercial vehicle or calling a professional transport service is always the smarter, safer call.

Why the 50 kg Limit? That number isn't arbitrary. It's a risk calculation. The confined, poorly ventilated space of a car makes any gas leak exponentially more dangerous than it would be in a commercial van or on an open truck bed.

Absolutely. This is one rule that has zero wiggle room. The valve is the weakest point on a cylinder, and when it’s laid flat, it's dangerously exposed to impacts from shifting cargo or, worse, an accident.

ADR regulations are perfectly clear: a heavy-duty, screw-on valve cap must be on tight during transport. Its only job is to shield that valve from damage or being sheared right off. A snapped valve turns a cylinder into an unguided, high-pressure missile. Moving a cylinder without its cap isn't just a bad idea; it's a serious safety and legal breach.

By far, the most common and dangerous error is using weak or improper restraints. Just laying a cylinder on the floor and hoping its weight will hold it is asking for trouble. A sudden stop or a sharp turn generates enough force to send that cylinder flying.

Another classic mistake is grabbing old ropes or bungee cords. Bungee cords are designed to stretch—the exact opposite of what you need. They have no business securing a heavy, high-pressure load.

Here’s how to do it right:

Yes, and it’s critical to know which ones. While most standard compressed gases can be transported horizontally if you follow all the rules, a few are strict exceptions.

Acetylene is the number one no-go. It must always be transported and stored perfectly upright. The reason is that acetylene gas is dissolved in a special acetone solvent held within a porous mass inside the cylinder. If you lay it down, that liquid acetone can separate, creating pockets of pure, unstable acetylene gas that could lead to explosive decomposition.

Cryogenic liquids, like liquid nitrogen, are another. They should also travel upright. This keeps the pressure relief valve at the top clear of the super-cold liquid, preventing it from malfunctioning or freezing shut, which could cause a catastrophic pressure build-up. Always, always check the specific transport rules for the exact gas you're handling before you even think about loading it.

For state-of-the-art cryogenic transport solutions that meet rigorous ADR and medical licensing standards, trust Cryonos GmbH. Our vessels are engineered for maximum safety and reliability, ensuring your sensitive biological samples and industrial gases are handled with care. Explore our complete range of products at https://www.cryonos.shop.